http://www.thenation.com/article/178344/distorting-russia#

Stephen F. Cohen: Leaked Tape Suggests U.S. Was Plotting Coup in Ukraine

The degradation of mainstream American press coverage of Russia, a country still vital to US national security, has been under way for many years. If the recent tsunami of shamefully unprofessional and politically inflammatory articles in leading newspapers and magazines—particularly about the Sochi Olympics, Ukraine and, unfailingly, President Vladimir Putin—is an indication, this media malpractice is now pervasive and the new norm.

There are notable exceptions, but a general pattern has developed. Even in the venerable New York Times and Washington Post, news reports, editorials and commentaries no longer adhere rigorously to traditional journalistic standards, often failing to provide essential facts and context; to make a clear distinction between reporting and analysis; to require at least two different political or “expert” views on major developments; or to publish opposing opinions on their op-ed pages. As a result, American media on Russia today are less objective, less balanced, more conformist and scarcely less ideological than when they covered Soviet Russia during the Cold War.

The history of this degradation is also clear. It began in the early 1990s, following the end of the Soviet Union, when the US media adopted Washington’s narrative that almost everything President Boris Yeltsin did was a “transition from communism to democracy” and thus in America’s best interests. This included his economic “shock therapy” and oligarchic looting of essential state assets, which destroyed tens of millions of Russian lives; armed destruction of a popularly elected Parliament and imposition of a “presidential” Constitution, which dealt a crippling blow to democratization and now empowers Putin; brutal war in tiny Chechnya, which gave rise to terrorists in Russia’s North Caucasus; rigging of his own re-election in 1996; and leaving behind, in 1999, his approval ratings in single digits, a disintegrating country laden with weapons of mass destruction. Indeed, most American journalists still give the impression that Yeltsin was an ideal Russian leader.

Since the early 2000s, the media have followed a different leader-centric narrative, also consistent with US policy, that devalues multifaceted analysis for a relentless demonization of Putin, with little regard for facts. (Was any Soviet Communist leader after Stalin ever so personally villainized?) If Russia under Yeltsin was presented as having legitimate politics and national interests, we are now made to believe that Putin’s Russia has none at all, at home or abroad—even on its own borders, as in Ukraine.

Russia today has serious problems and many repugnant Kremlin policies. But anyone relying on mainstream American media will not find there any of their origins or influences in Yeltsin’s Russia or in provocative US policies since the 1990s—only in the “autocrat” Putin who, however authoritarian, in reality lacks such power. Nor is he credited with stabilizing a disintegrating nuclear-armed country, assisting US security pursuits from Afghanistan and Syria to Iran or even with granting amnesty, in December, to more than 1,000 jailed prisoners, including mothers of young children.

Not surprisingly, in January The Wall Street Journal featured the widely discredited former president of Georgia, Mikheil Saakashvili, branding Putin’s government as one of “deceit, violence and cynicism,” with the Kremlin a “nerve center of the troubles that bedevil the West.” But wanton Putin-bashing is also the dominant narrative in centrist, liberal and progressive media, from the Post, Times and The New Republic to CNN, MSNBC and HBO’s Real Time With Bill Maher, where Howard Dean, not previously known for his Russia expertise, recently declared, to the panel’s approval, “Vladimir Putin is a thug.”

The media therefore eagerly await Putin’s downfall—due to his “failing economy” (some of its indicators are better than US ones), the valor of street protesters and other right-minded oppositionists (whose policies are rarely examined), the defection of his electorate (his approval ratings remain around 65 percent) or some welcomed “cataclysm.” Evidently believing, as does the Times, for example, that democrats and a “much better future” will succeed Putin (not zealous ultranationalists growing in the streets and corridors of power), US commentators remain indifferent to what the hoped-for “destabilization of his regime” might mean in the world’s largest nuclear country.

Certainly, The New Republic’s lead writer on Russia, Julia Ioffe, does not explore the question, or much else of real consequence, in her nearly 10,000-word February 17 cover story. Ioffe’s bannered theme is devoutly Putin-phobic: “He Crushed His Opposition and Has Nothing to Show for It But a Country That Is Falling Apart.” Neither sweeping assertion is spelled out or documented. A compilation of chats with Russian-born Ioffe’s disaffected (but seemingly not “crushed”) Moscow acquaintances and titillating personal gossip long circulating on the Internet, the article seems better suited (apart from some factual errors) for the Russian tabloids, as does Ioffe’s disdain for objectivity. Protest shouts of “Russia without Putin!” and “Putin is a thief!” were “one of the most exhilarating moments I’d ever experienced.” So was tweeting “Putin’s fucked, y’all.” Nor does she forget the hopeful mantra “cataclysm seems closer than ever now.”

* * *

For weeks, this toxic coverage has focused on the Sochi Olympics and the deepening crisis in Ukraine. Even before the Games began, the Times declared the newly built complex a “Soviet-style dystopia” and warned in a headline, Terrorism and Tension, Not Sports and Joy. On opening day, the paper found space for three anti-Putin articles and a lead editorial, a feat rivaled by the Post. Facts hardly mattered. Virtually every US report insisted that a record $51 billion “squandered” by Putin on the Sochi Games proved they were “corrupt.” But as Ben Aris of Business New Europe pointed out, as much as $44 billion may have been spent “to develop the infrastructure of the entire region,” investment “the entire country needs.”

Overall pre-Sochi coverage was even worse, exploiting the threat of terrorism so licentiously it seemed pornographic. The Post, long known among critical-minded Russia-watchers as Pravda on the Potomac, exemplified the media ethos. A sports columnist and an editorial page editor turned the Olympics into “a contest of wills” between the despised Putin’s “thugocracy” and terrorist “insurgents.” The “two warring parties” were so equated that readers might have wondered which to cheer for. If nothing else, American journalists gave terrorists an early victory, tainting “Putin’s Games” and frightening away many foreign spectators, including some relatives of the athletes.

The Sochi Games will soon pass, triumphantly or tragically, but the potentially fateful Ukrainian crisis will not. A new Cold War divide between West and East may now be unfolding, not in Berlin but in the heart of Russia’s historical civilization. The result could be a permanent confrontation fraught with instability and the threat of a hot war far worse than the one in Georgia in 2008. These dangers have been all but ignored in highly selective, partisan and inflammatory US media accounts, which portray the European Union’s “Partnership” proposal benignly as Ukraine’s chance for democracy, prosperity and escape from Russia, thwarted only by a “bullying” Putin and his “cronies” in Kiev.

Not long ago, committed readers could count on The New York Review of Books for factually trustworthy alternative perspectives on important historical and contemporary subjects. But when it comes to Russia and Ukraine, the NYRB has succumbed to the general media mania. In a January 21 blog post, Amy Knight, a regular contributor and inveterate Putin-basher, warned the US government against cooperating with the Kremlin on Sochi security, even suggesting that Putin’s secret services “might have had an interest in allowing or even facilitating such attacks” as killed or wounded dozens of Russians in Volgograd in December.

Knight’s innuendo prefigured a purported report on Ukraine by Yale professor Timothy Snyder in the February 20 issue. Omissions of facts, by journalists or scholars, are no less an untruth than misstatements of fact. Snyder’s article was full of both, which are widespread in the popular media, but these are in the esteemed NYRB and by an acclaimed academic. Consider a few of Snyder’s assertions:

§ ”On paper, Ukraine is now a dictatorship.” In fact, the “paper” legislation he’s referring to hardly constituted dictatorship, and in any event was soon repealed. Ukraine is in a state nearly the opposite of dictatorship—political chaos uncontrolled by President Viktor Yanukovych, the Parliament, the police or any other government institution.

§ ”The [parliamentary] deputies…have all but voted themselves out of existence.” Again, Snyder is alluding to the nullified “paper.” Moreover, serious discussions have been under way in Kiev about reverting to provisions in the 2004 Constitution that would return substantial presidential powers to the legislature, hardly “the end of parliamentary checks on presidential power,” as Snyder claims. (Does he dislike the prospect of a compromise outcome?)

§ ”Through remarkably large and peaceful public protests…Ukrainians have set a positive example for Europeans.” This astonishing statement may have been true in November, but it now raises questions about the “example” Snyder is advocating. The occupation of government buildings in Kiev and in Western Ukraine, the hurling of firebombs at police and other violent assaults on law enforcement officers and the proliferation of anti-Semitic slogans by a significant number of anti-Yanukovych protesters, all documented and even televised, are not an “example” most readers would recommend to Europeans or Americans. Nor are they tolerated, even if accompanied by episodes of police brutality, in any Western democracy.

§ ”Representatives of a minor group of the Ukrainian extreme right have taken credit for the violence.” This obfuscation implies that apart perhaps from a “minor group,” the “Ukrainian extreme right” is part of the positive “example” being set. (Many of its representatives have expressed hatred for Europe’s “anti-traditional” values, such as gay rights.) Still more, Snyder continues, “something is fishy,” strongly implying that the mob violence is actually being “done by russo-phone provocateurs” on behalf of “Yanukovych (or Putin).” As evidence, Snyder alludes to “reports” that the instigators “spoke Russian.” But millions of Ukrainians on both sides of their incipient civil war speak Russian.

§ Snyder reproduces yet another widespread media malpractice regarding Russia, the decline of editorial fact-checking. In a recent article in the International New York Times, he both inflates his assertions and tries to delete neofascist elements from his innocuous “Ukrainian extreme right.” Again without any verified evidence, he warns of a Putin-backed “armed intervention” in Ukraine after the Olympics and characterizes reliable reports of “Nazis and anti-Semites” among street protesters as “Russian propaganda.”

§ Perhaps the largest untruth promoted by Snyder and most US media is the claim that “Ukraine’s future integration into Europe” is “yearned for throughout the country.” But every informed observer knows—from Ukraine’s history, geography, languages, religions, culture, recent politics and opinion surveys—that the country is deeply divided as to whether it should join Europe or remain close politically and economically to Russia. There is not one Ukraine or one “Ukrainian people” but at least two, generally situated in its Western and Eastern regions.

Such factual distortions point to two flagrant omissions by Snyder and other US media accounts. The now exceedingly dangerous confrontation between the two Ukraines was not “ignited,” as the Times claims, by Yanukovych’s duplicitous negotiating—or by Putin—but by the EU’s reckless ultimatum, in November, that the democratically elected president of a profoundly divided country choose between Europe and Russia. Putin’s proposal for a tripartite arrangement, rarely if ever reported, was flatly rejected by US and EU officials.

Please support our journalism. Get a digital subscription for just $9.50!

But the most crucial media omission is Moscow’s reasonable conviction that the struggle for Ukraine is yet another chapter in the West’s ongoing, US-led march toward post-Soviet Russia, which began in the 1990s with NATO’s eastward expansion and continued with US-funded NGO political activities inside Russia, a US-NATO military outpost in Georgia and missile-defense installations near Russia. Whether this longstanding Washington-Brussels policy is wise or reckless, it—not Putin’s December financial offer to save Ukraine’s collapsing economy—is deceitful. The EU’s “civilizational” proposal, for example, includes “security policy” provisions, almost never reported, that would apparently subordinate Ukraine to NATO.

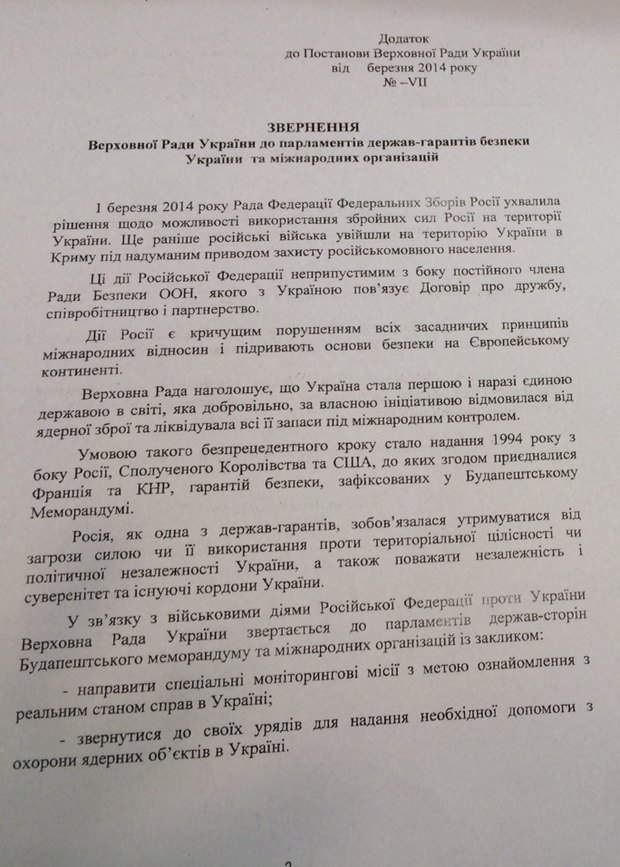

Any doubts about the Obama administration’s real intentions in Ukraine should have been dispelled by the recently revealed taped conversation between a top State Department official, Victoria Nuland, and the US ambassador in Kiev. The media predictably focused on the source of the “leak” and on Nuland’s verbal “gaffe”—“Fuck the EU.” But the essential revelation was that high-level US officials were plotting to “midwife” a new, anti-Russian Ukrainian government by ousting or neutralizing its democratically elected president—that is, a coup.

Americans are left with a new edition of an old question. Has Washington’s twenty-year winner-take-all approach to post-Soviet Russia shaped this degraded news coverage, or is official policy shaped by the coverage? Did Senator John McCain stand in Kiev alongside the well-known leader of an extreme nationalist party because he was ill informed by the media, or have the media deleted this part of the story because of McCain’s folly?

And what of Barack Obama’s decision to send only a low-level delegation, including retired gay athletes, to Sochi? In August, Putin virtually saved Obama’s presidency by persuading Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to eliminate his chemical weapons. Putin then helped to facilitate Obama’s heralded opening to Iran. Should not Obama himself have gone to Sochi—either out of gratitude to Putin, or to stand with Russia’s leader against international terrorists who have struck both of our countries? Did he not go because he was ensnared by his unwise Russia policies, or because the US media misrepresented the varying reasons cited: the granting of asylum to Edward Snowden, differences on the Middle East, infringements on gay rights in Russia, and now Ukraine? Whatever the explanation, as Russian intellectuals say when faced with two bad alternatives, “Both are worst.”